1. The Highest Incarceration Rates in the World.

The Extreme Incarceration of Aboriginal people in Australia

Aboriginal people are being imprisoned at the highest recorded rate-by a long way-of any population in the world. These rates are higher than African Americans and other Indigenous populations including those of Canada and Aotearoa-New Zealand.

The numbers have kept on rising since the 1990s, since we started keeping more accurate records, so that now in early 2025 Aboriginal people are 17 times more likely to be locked up than other Australians.

At the same time prison rates for non-Aboriginal people are way lower- they are steady and are similar to other western countries.

Check out the Peak Prison blog for more details.

But it’s not just about the numbers, it’s about people. We talk about the ‘over-representation’ of Aboriginal people in prison in a way that sanitises what’s happening. It’s not just a few extra people in prison, it’s extreme incarceration.

Almost every Aboriginal family in Australia is affected by having close relatives in prison. And it has many consequences. It breaks spirits. It demoralises an entire population. It fuels more crime.

No matter how hard we look, it’s impossible to find a reason that justifies the extreme incarceration of Aboriginal people.

So why is this happening? Do more Aboriginal people deserve to be in prison? Are Aboriginal people more criminal than others?

We say that the answers are complex, that we have to address the root causes, that we have to understand the social determinants of incarceration and the effects of racism and colonisation. This is of course entirely true.

We know that there is not a simple change we can make to fix this. But by saying it is complex, we can miss the many significant things that we can do and need to do right now. By saying it is complex we risk setting our expectations too low and not look to the current systems and narratives that sustain the justice machine, a machine that relentlessly and carelessly over-processes Aboriginal people through it.

While the problem of Aboriginal over-incarceration by definition sits within the justice system, the solutions are fundamentally to be found within community, within our health and social services

As Australians, we like to see ourselves as fair people. Ultimately, we are aiming for a justice system that Aboriginal people in Australia can believe is fair, that we can all respect and trust, and that works to keep everybody safer. We do not have that now.

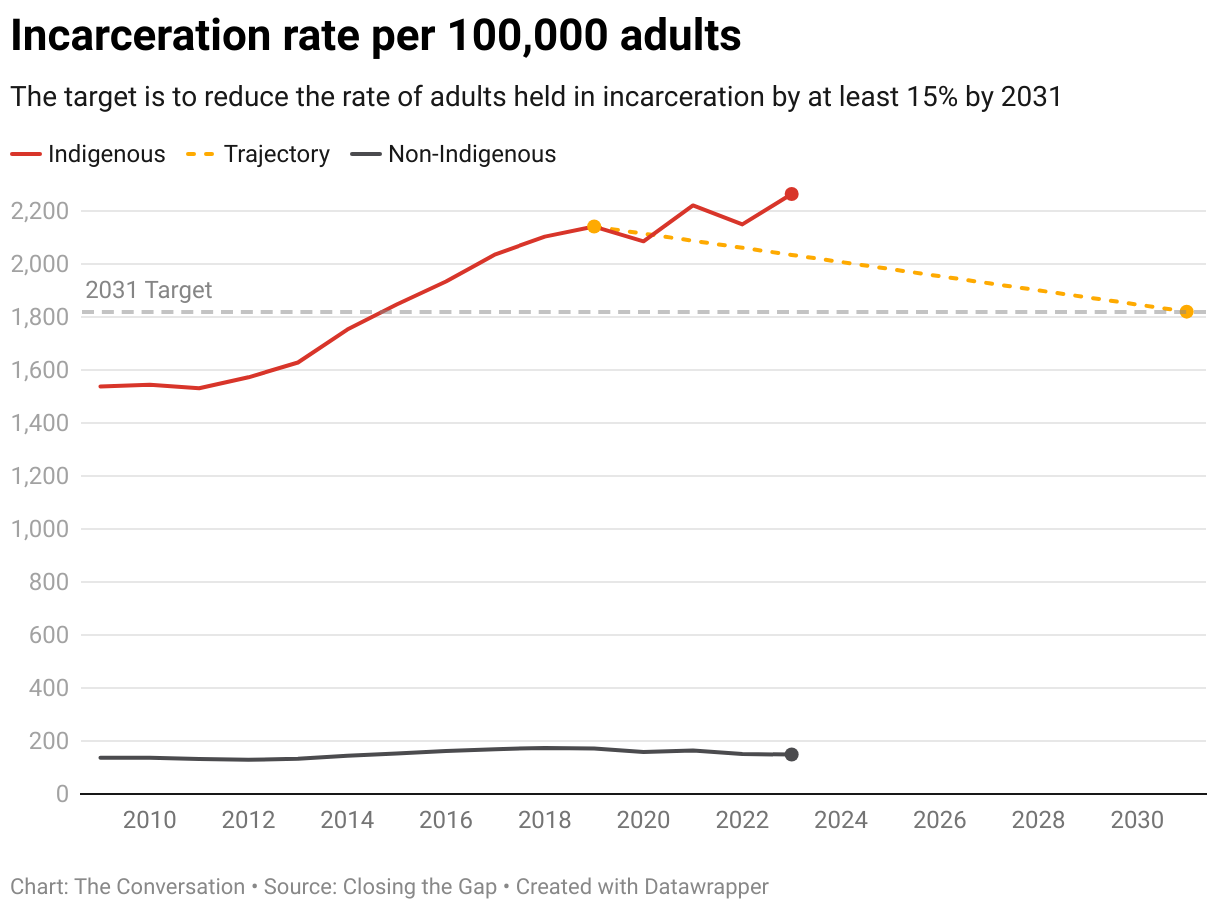

The current national Closing The Gap target seeks to reduce Aboriginal adults held in incarceration by 15% by 2031 from a 2019 baseline. In the past year alone rates have increased by 15%!

For true equity, with no ‘over-representation’ the reduction that needs to be achieved is over 90%.

Then, if we are really serious about matching European best practice and meeting our Human Rights obligations, we would have to halve again the national rates for everyone.

We have work to do.

HEALTH & WELLBEING

CONNECTION

vs

PRISON & PUNISHMENT

DISCONNECTION

2. Health vs Justice

Health and Imprisonment work in constant tension.

Health and wellbeing, as described by Aboriginal people, is about Connection -to community, to family, to culture and to country.

Imprisonment is about Disconnection from society.

In our Australian prisons and youth detention centres these two processes are basically working at cross purposes.

Prisons in Australia by design are unhealthy places. They are primarily places of punishment and exclusion. Security needs trump health needs every time.

We cannot meaningfully promote the wellbeing of prisoners when they are disconnected from community. In Australia a ‘healthy prison’ is a contradiction in terms. See We Can Do Much Better for a look at alternatives.

We can advocate for access to Medicare, clean needle programs or access to therapeutic programs; we can talk about the opportunities in prison to assess a captive population’s health needs, but we are fundamentally missing the point of what health is about. Health is largely constituted and sustained by healthy relationships. Prisons in Australia are not places that model or support healthy relationships.

In 2001, in one of the most comprehensive studies in the world at the time, NSW researchers conducted a study of the health of prisoners in their prisons.. See Inmate Health Survey. This study built on earlier work and included information about mental health and cognitive functioning. They found that overall prisoners were significantly less healthy than their counterparts in the community. Of particular note were the high levels of mental health problems, head injury, intellectual disability, hepatitis C and smoking.

Given the high turnover of people moving through prisons, prison health services are tasked mostly with managing the acute health risks for prisoners rather than the overall health needs. Even when chronic health concerns are identified and treated the chaotic path for many prisoners post-release means many are lost to follow up.

Health services in prisons have a constant fight to deliver a service. Services only really make sense when they are provided by in-reach from community, with an aim to establish positive relationships, and to build connected pathways to the community health and social services that can be sustained post-release, where the real work begins.

For Aboriginal prisoners, the sensible approach is for health and wellbeing services to be provided by Aboriginal controlled health services. However, apart from a few isolated examples, Aboriginal controlled services are grossly under-resourced to do this demanding work, both the prison-in reach and the community-based integrated justice support. The task is made even more difficult by the work involved in un-doing the harms and lasting negative impacts resulting from periods of incarceration. The first few months post-release are an extremely high risk time.

When we consider mental health, or more broadly brain health in prisons, we open up a whole world of pain. Many prisoners have substantial undiagnosed mental health and cognitive concerns before entering prison, often not acknowledged or treated. See Mental Health, Cognitive Health, Trauma and Substance Misuse. Forensic units can see and treat only a fraction of the clients at risk. Offenders in regional and remote locations are particularly poorly served.

3. The Health of Indigenous Young Adults in Australia.

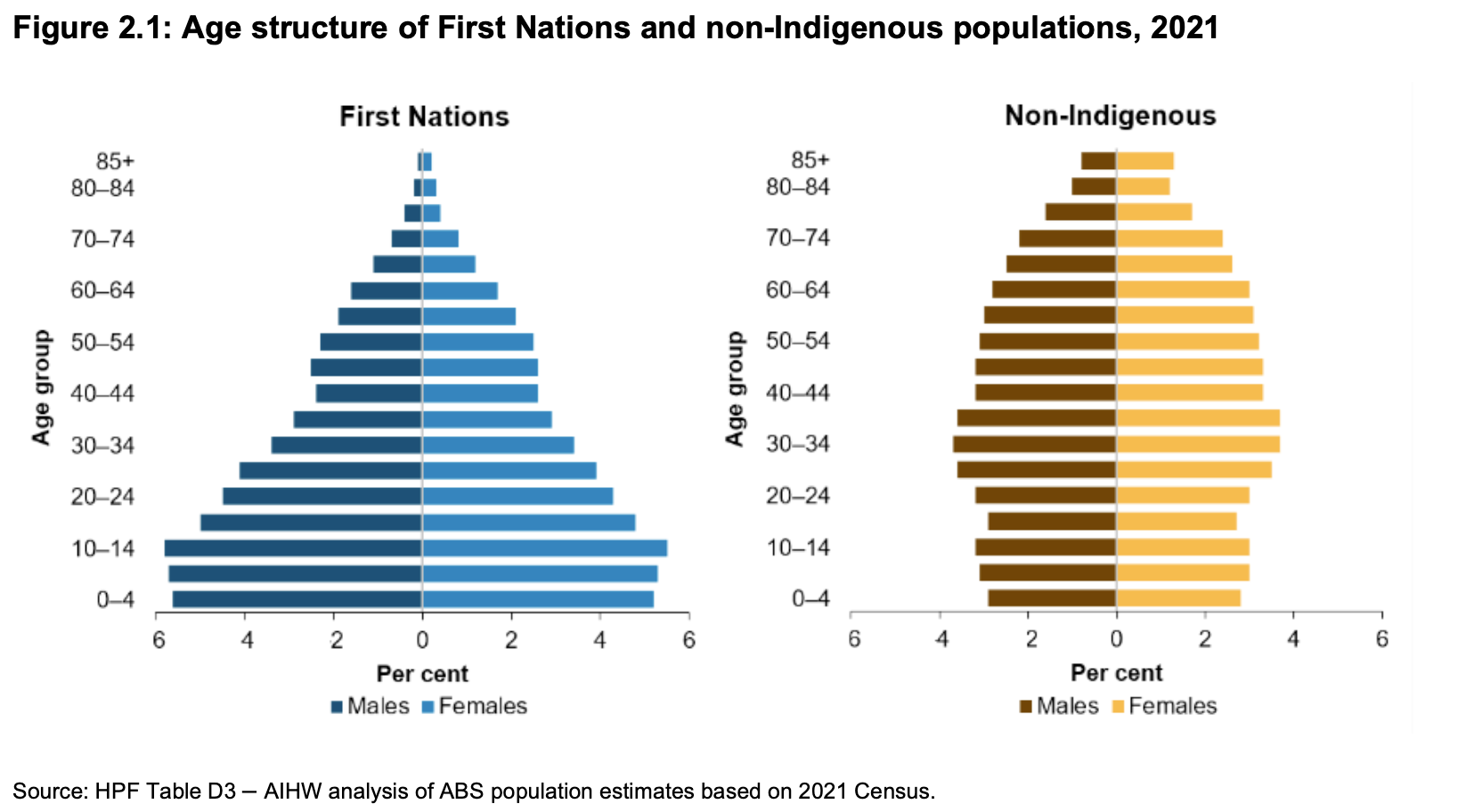

When we look at the population pyramids comparing Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal populations at each age group, shown here in the adjacent Figure 2.1, we see some really important differences. In the blue diagram on the left representing the Aboriginal population, there is a strong drop-off in population for Aboriginal people from age 14-44. This doesn’t happen for the non-Aboriginal community, shown in the orange pyramid on the right. In a healthy population very few people die in early adulthood and this shows as nearly vertical sides in the age pyramid.

The diagram highlights the many premature and largely preventable deaths happening for Aboriginal young people and young adults, people who should be in their prime.

This recent pyramid for Aboriginal people in Australia in 2021 still has a profile very similar to those of some of the poorest countries in the world, except it does not show the same decline in the first 10 years of life usually seen in poorer developing countries.

In remote communities life expectancy for Aboriginal people is still about 12 years lower than the Australian average, many deaths being preventable deaths in younger people.

In urban areas, the life expectancy gap is about 8 years lower.

The age range, from 14-44 is also the time for peak justice involvement.

Focusing a lot more attention on the health of Aboriginal young people is an absolute priority for health services. Young people and young adults remain highly vulnerable, with deaths not so much from chronic disease, but from mental health problems, accidents, injuries and substance misuse. The impacts of justice involvement is a critical consideration for reducing morbidity and mortality for this population.

https://www.aihw.gov.au/suicide-self-harm-monitoring/population-groups/justice

https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/getattachment/79e5f9c5-f5b9-4a1f-8df6-187f267f6817/hpf_summary-report-aug-2024.pdf

4. Mental Health, Cognitive Health, Trauma and Substance Misuse

The interconnected nature of Brain health requires a very different approach to assessment and supports..

Aboriginal understandings of mental health are grounded in the guiding health concept of Social and Emotional Well-being (SEWB). The concept acknowledges connectedness, holistic ideas of health and the impacts of trauma and loss, and of Aboriginal rights and strengths.

Past detailed studies of the mental health of prisoners in New South Wales have shown very high levels of mental health problems, with up to 80% of prisoners having experienced any psychiatric illness in the past 12 months. Rates of psychosis, substance use disorders, personality disorders and head injury in prisoners were all 8-12 times higher than average community rates. [Butler et al]

The health of our brains is shaped and sustained by a range of interconnected factors that determine how we respond to the world around us.

In our whitefella world, when we talk about mental health we are describing only one part of the story. More recently people have started talking about ‘Brain Health’ in an attempt to talk more inclusively about what shapes our mental, cognitive and emotional wellbeing.

The adjacent diagram, illustrates a ‘trans-diagnostic’ view of Brain Health. It attempts to convey some of the interconnected, mutually reinforcing, frequently co-existing domains that shape the whitefella diagnostic view of our mental functioning. All four domains impact on our overall cognitive functioning, particularly affecting the pre-frontal cortex of the brain, responsible for decision-making and problem-solving, affecting how a person responds to their outside world.

For Aboriginal communities, co-morbidity and complexity are often the norm, and diagnostic clarity may be difficult to achieve. Cultural and social disconnection, socioeconomic disadvantage and justice involvement further compound the picture.

While the diagram itself is not surprising, one of the main challenges here is that each of the four domains is managed by a different mainstream service sector, each with its own specialty approaches to treatment and care.

On release, prisoners are commonly referred to multiple services for follow-up, each acting independently of the others, setting up an entirely unrealistic and unhelpful response plan, particularly if the client is already homeless on release. On top of Centrelink, housing services and community corrections appointments, a person can be referred to attend mental health, drug counselling and disability supports. Each appointment can require several public transport trips. For most, the person in the middle and their family risk being overwhelmed with ‘help’ that is not integrated and is ultimately confusing and counter-productive. Then, there is the too common practice of blaming the client if they do not engage. For some, non-engagement results in return to prison.

At the other end of the spectrum there is the risk for clients with prison histories and complex needs being excluded entirely from services because of their complexity and concerns about perceived risks to staff, often without the necessary information available to assess risk. People can be shunted around the systems without ever getting the support they need.

Too often prisoners are ‘risk-managed out of care.

Acquired Brain Injury (ABI):

Australian research studies indicate that around 42% of men in prison and 33% of women in prison have an Acquired Brain Injury, compared with 2% in the community. The factors that lead to an increased risk of ABI can overlap with factors that lead to aimprisonment, for example early exposure to traumatic stress; leaving education early; risk-taking behaviour early in life; homelessness and its associated vulnerabilities; continued misuse of alcohol or other drugs and exposure to violence in intimate relationships.

ABI can result in multiple disabilities arising from damage to the brain after birth. It is often called the invisible injury, because many people with an ABI do not have obvious physical impairments. Symptoms of ABI vary greatly from one person to the next; they can include physical, emotional, behavioural, language and cognitive difficulties. ABI can be caused by an injury to the head, medical conditions affecting the brain; low oxygen to the brain or long-term, heavy drug or alcohol use.

Traumatic Stress/ Complex Trauma/Collective Trauma: Aboriginal communities have continually described the ongoing impacts of both historical and contemporary traumatic experience ever since colonisation. The consequences of complex and collectively experienced trauma affect the daily lives of individuals and whole communities. Traumatic experience can compound psychosocial impairment from other causes and greatly impact on a person’s capacity to function well in their community. Symptoms like anxiety and depression, suicidal ideation, anger, aggression can all be expressions of traumatic stress. Creating safe, nurturing, communities is an essential step in healing from trauma.

Prisons are also an independent risk factor for suicide, as is the immediate post-release period. Showing vulnerability of any kind in prison places a prisoner at risk of harm. For Australians between the ages of 15 and 44 years, suicide is the leading cause of death (AIHW, 2022a). The suicide rate in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is twice that of their non-Indigenous counterparts (ABS, 2022).

Providing the right integrated services to respond to the complex brain health needs of prisoners is skilled work. It required skilled well-resourced, culturally-safe teams embedded within Aboriginal-controlled community-based services.

More to follow on this.

The Brain Health Complex

One of the main challenges here is that each of the four domains is managed by a different mainstream service sector, each with its own specialty approaches to treatment and care.

Some Brain Health Facts

Up to 40% of victims of family violence attending hospital sustain a Brain Injury.

People with Post-Traumatic Stress experience significantly higher rates of psychosis when compared to the wider community.

Over 60% of people in prison are estimated to have an Acquired Brain Injury.

Life expectancy for people with major Mental Health issues is 10-20 years less than the general population, mostly due to physical comorbidities, particularly diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Much of this gap is preventable.

People with major traumatic childhood adverse events have worse physical health later in life and a decreased life expectancy.

1. Brain Injury Australia The Prevalence of Acquired Brain Injury Among Victims and Perpetrators of Family Violence Brain Injury Australia 2018

2. Seedat, S et al Linking Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Psychosis: A Look at Epidemiology, Phenomenology, and Treatment. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease Vol 191:10. October 2003.

3. Jesuit Social Services /RMIT Enabling Justice Project Consultation paper: People living with Acquired brain injury using their experiences of the criminal justice system to achieve systemic change. June 2016.

4. Firth, J et al The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness.The Lancet Psychiatry Commission Vol 6 :8 Aug 2019 pp675-712.

5. American Academy of Pediatrics Adverse Childhood Experiences and the Lifelong Consequences of Trauma 2014 Accessed at: https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/ttb_aces_consequences.pdf

5. Time For A New Plan

The Royal Commission Into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC) Recommendations are not enough.

The Recommendations of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC) which were handed down in 1991, to examine concerns about the increasing number of Aboriginal Deaths in Custody and determine whether there were correctional practices that were contributing to this. The Commission never had the brief to address over-incarceration.

Early in it’s inquiry the Commission concluded that ‘Aboriginal people in custody do not die at a greater rate than non-Aboriginal people in custody … what is overwhelmingly different is the rate at which Aboriginal people come into custody, compared with the rate of the general community’.

The Commission, within their resource and time constraints, attempted to respond in some part to the issues shaping over-incarceration, but were only able to do so in quite general terms.

Of the 339 recommendations in the RCIADIC report over 50 recommendations looked at improving in-prison practices.

Many of the recommendations that related specifically to reducing deaths in custody have been substantially implemented, bringing both some improvements and some bad news. In the 27 years following the release of the Royal Commission report, the mortality rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in custody has halved. However, over the same time, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander share of the prison population has more than doubled and continues to rise. Net effect, no improvement.

In fact, there are now more Aboriginal deaths in custody than there were at the time of the Royal Commission. In 2023-24 there were 24 Indigenous deaths in custody. Roughly half of the deaths were deemed from natural causes while nearly half were from hanging and related complications.

The RCIADIC also made more general recommendations about improving community-based responses. While these recommendations are sound most are too general for anyone to be held to account to deliver on them.

Over 100 of the recommendations relate to social and community measures that require a foundational shift in the way we see and respond to many of the determinants of incarceration.

The RCIADIC was a deeply important consultation process and a genuine conversation between the government of the time and the Indigenous people of Australia. Its report included ground-breaking observations and recommendations that remain relevant today, not only about deaths in custody but the broader issues surrounding Aboriginal incarceration. But after thirty years of partial implementation the situation has not improved for Aboriginal families.

Advocates across the country have continued to call for the full implementation of all 339 recommendations. However, it’s highly questionable that the document still has political currency or that the recommendations provide the targeted solutions we now need.

A federally commissioned review of the implementation of the RCIADIC recommendations conducted in 2018 by Deloitte Access Economics concluded that 78% of the 339 recommendations have been fully or mostly implemented and that 91% of the recommendations for which government has some responsibility had been satisfactorily implemented.

This finding has been strongly challenged by many Indigenous leaders including in a 2021 critique by the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research who expressed concerns about the methodology and data sources used by the review, stating that it obscured whether any of the responses taken had actually achieved any positive outcomes.

A lot has happened since the release of the RCIADIC report. There are potential solutions and ways of thinking now that were not readily available to the Commission in the early 1990s.

Collectively, we have learned a lot about better justice since then, even if we haven’t applied it widely in Australia.

We have better understandings of neurocognitive development and its effects on young people. We know more about links between mental health, trauma, acquired brain Injury and justice.

We know more about the ways that mental health issues and acquired brain Injury affect people and can impact justice involvement; we have better ways of treating these conditions in the community.

We have learned about the impacts of trauma in shaping the lives of those we imprison.

We have more information about the positive achievements and constraints of therapeutic jurisprudence, solution-focused courts, Koori Courts, Restorative Justice and Justice Reinvestment as applied in Australia.

We have successful western European models with low incarceration and high community safety to draw on.

Perhaps we also better understand the intentional role of the colonising voices in Australian politics that sustain Aboriginal over-incarceration.

The point is that now, 30 years on, there are countless ways available to us to do better. No longer is it OK just to try to make prisons safe for Aboriginal people. We are long overdue for a re-think of how we do justice, how we can keep Aboriginal people out of prison and reduce the damage that prisons do to so many Aboriginal people, their families and our Australian society.

Our current approach is piecemeal and half-hearted.

Justice is always political. It is governments who need to shape the policies and lead the change, but we, the Australian people need to demand the change.

Our federal government defers to the states, saying that each state and territory determines their own justice policies, but extreme Indigenous incarceration is an issue in every state and territory. Also of major significance, is that while incarceration is a justice responsibility, most of the solutions lie with health and social services particularly the Aboriginal Community-Controlled sector and programs like the National Disability Insurance Scheme that are federally funded.

Together, we need to chart the way forward in clear terms.

We need a New Plan.

https://www.austlii.edu.au/au/other/IndigLRes/rciadic/national/vol5/5.html

https://www.niaa.gov.au/resource-centre/review-implementation-royal-commission-aboriginal-deaths-custody

https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-12/sr49_deaths_in_custody_2023-24.pdf

https://caepr.cass.anu.edu.au/research/publications/30-years-royal-commission-aboriginal-deaths-custody-recommendations-remain

"When prisoners feel that they are not part of the 'us' in society, what motivation do they have to follow the laws and norms of the society that has rejected them?"

6. More Prisons Don’t Mean Less Crime

Locking up more people does not make communities safer.

If we are already locking up more people than anywhere else in the world and it isn’t working, then how can we possibly expect that tougher sentencing is going to help. There’s increasing evidence that prisons, as they are currently run can actually be criminogenic, meaning they can increase the risk of offending for some people rather than reduce crime.

Most recent figures show that for Aboriginal prisoners 76% have been in prison before. This means that for a big majority prison has not helped with rehabilitation or staying out of trouble with the law.

Keeping communities safe and upholding the rights of offenders are often held up as opposing aims, particularly at election time. Listen to the media coverage and you will hear people arguing across the divide, often reduced to a ‘Tough on Crime’ vs ‘Soft on Crime’ approaches. The soft-on-crimers’, those who argue against locking up more First Nations people, (including most experts and most service providers and most of the Aboriginal community) are charged with caring more about the welfare of criminals than the wellbeing of the community.

‘Tough on crimers’ will reasonably ask, ‘What about the victims?’

‘Soft on crimers’ will reasonably ask, ‘What about the rights and wellbeing of the prisoners?’

The divide may help win elections for 'tough on crimers’ but it doesn’t contribute to better justice. Any good response to reducing Aboriginal incarceration rates understands that improving community safety and improving offender wellbeing are not opposing forces, they are tightly linked parts of the same story.

Achieving low crime and low imprisonment are entirely possible for any democratic nation.

There are many highly successful international examples, particularly in Europe, that show the benefits to community of supporting offender wellbeing.

Norway has a world-leading justice systems that embraces a therapeutic model prioritising the health, welfare and community connection of those caught up in the justice system. The principle of’ normality’, that prisoners have the same rights as all other citizens, underwrites the system. Norway has a community who feel safe. Achieving these outcomes demanded a major shake-up of justice policy and legislation, with strong advocacy from criminologists and community over many years.

The Indigenous population of Norway, the Sami, are not over-represented in their prisons. More to come on the strengths and possible limitations of Norway’s system later.

A good system acknowledges that prisoners and offenders remain part of the community. It helps offenders feel connected to community in positive ways, and helps community feel connected to its prisoners!

The vast majority of prisoners in Australia have sentences less than 2-3 years. Over 95% of prisoners have sentences of 5 years. They will all be returning to communities rehabilitated or not.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-06-04/australia-broken-prison-system-norway-face-facts/103926876

Prisoners in Australia 2024

https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/prisoners-australia/latest-release#aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-prisoners

https://www.gallup.com/analytics/356996/gallup-global-safety-research-center.aspx

https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1177&context=eilr

6. About Trauma

7. Youth Justice

Good Kid Mad System

8. We Can Do Better

WATCH THIS SPACE.

More to Come